“Power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” – Mao Zedong

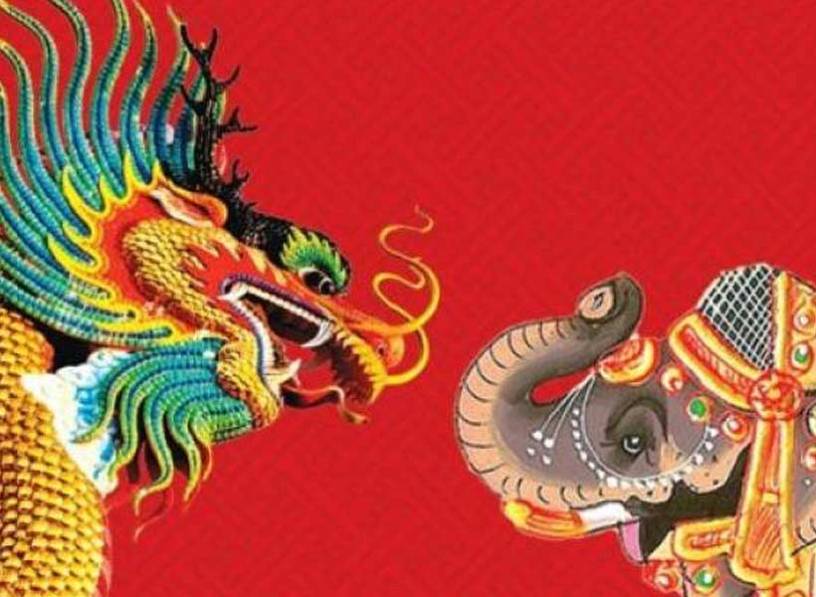

This is the mantra that shaped the Chinese geopolitical scene in the 50s. But China today has asserted its global dominance not just on the might of arms but also owing to her visionary leaders who implemented prudent and pioneering foreign and economic policies. The current president of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping is being lauded as the leader who will establish China as the de-facto world superpower. Today China is world’s second-largest economy and on its way to becoming number one.

Recently after the Doklam standoff, there seems to be a paranoia that has gripped the Indian community about China’s ever-increasing power and influence in South Asia. This article attempts to scrutinize this issue.

Creditor Imperialism, a fairly new buzzword in Sri Lanka, is making waves in the political scenario of the country. The frenzy surrounding it is reasonable as Lanka’s half-baked policies and projects to develop its infrastructure has plunged it deep into a pit of external debt, pushing the country to the brink of bankruptcy and prompting an IMF bailout.

The official estimate of what Sri Lanka currently owes its financiers is $64.9 billion — $8 billion of which is owned by China. The country’s debt-to-GDP currently stands around 75% and 95.4% of all government revenue is currently going towards debt repayment. Under President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, both of whom came to office at the beginning of 2015, domestic debt grew by 12% and external debt by 25% without any new large-scale infrastructure projects.

Most of this debt came about when Mahinda Rajapaksa, the sixth president of Sri Lanka, initiated large-scale, expensive infrastructure projects(including a cricket stadium) in his sparsely populated southern home district with Chinese loans. This was done even though the economic infeasibility of the projects was known. Between 2009 and 2014 Sri Lanka’s total government debt tripled and external debt doubled. The Maithripala Sirisena government that followed didn’t change the status quo either, given the fact that he campaigned on a promise to scrutinize recent foreign investments.

Inevitable as it was, the port, airport, and stadiums that were a part of the infrastructural investments became more of a liability than an asset. The 34000-seat stadium hosted a single professional cricket match in 2 years and the $209 million Mattala airport was dubbed as the ‘Emptiest Airport in the World’. The $1.4bn Hambantota port yielded such fewer returns on investments that the Lankan government was forced to sell 80 % stakes in the port to the state-controlled China Merchants Port Holdings. The construction of the port took place from the raw materials supplied by the Chinese; the workforce involved was majorly Chinese along with Chinese machinery pump-priming their industries.

Apart from the Chinese strategy of converting loans to equity in Sri Lanka, the strategic position of the Hambantota port, which is now under Chinese control, is a matter of grave concern for Indian security. The port, believed to be a part of the Chinese One Belt One Road (OBOR) policy, lies on a key-shipping route which sees oil shipments travel from the Middle East and carries 80% of China’s fuel imports. In addition, the proximity of the port to the Sukhoi air-base in Thanjavur is a matter of concern for the Indian officials.

Chinese haven’t made investments in Pakistan and Sri Lanka alone. In 2011, China invested $3bn in Lumbini, Nepal for an infrastructural overhaul of the town. A year before this investment was made, the GDP of the country was $35bn, thereby making the investment roughly 10% of the country’s GDP. This was enormous by any standards.

The Chinese also signed a MoU with Bangladesh in 2016 where Bangladesh is set to receive $24.45 billion in bilateral assistance for 34 projects and programs combined with a further $13.6 billion in Chinese investment in the form of 13 joint ventures. The sum of $38.05 billion is the biggest ever assistance pledged to Bangladesh by any single country.

What does China stand to gain from such hefty investments?

Clearly, China is seeking cultural, political, and economic clout. Nepal and Bangladesh are important buffer states between India and China. The primary concern of China in Nepal is its border with the Tibet autonomous region which is a hotbed of domestic instability. On the other hand, Bangladesh is an important trade route for Chinese products to reach the Indian market given that the routes through Pakistan, Afghanistan and Arunachal Pradesh pose political roadblocks. Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are important nations in the ‘String of Pearls’ theory, through which China plans to strengthen its maritime influence in the Indian Ocean and add an extra layer of security to its Malacca Strait route.

China is already the biggest foreign investor in Nepal with investments amounting to more than three times their Indian counterpart. Beijing has pledged $8.3 billion to build roads and hydropower plants in Nepal even as Indian commitments remain nearly $317 million. As part of its Belt and Road Initiative(BRI), China is looking into the possibility of building railway routes at an estimated cost of $8 billion. Now with a hopefully-steady leftist government in Nepal and a pro-China head of the government, China is hopeful of a stepped-up pace in the OBOR projects which had been stalled for a long time. Following the severance of Indo-Nepal relations in 2014 when all trade was blocked between the two, China now stands to gain from this.

Some see this as a strategic containment of India to check India’s regional dominance in South Asia. This claim has its merits, not only because of China’s financial involvement in the region but also because between 2011 and 2015, 71 percent of Chinese arms exports were to Pakistan, Myanmar, and Bangladesh. Bangladesh being the second largest recipient of Chinese arms in the world with Beijing supplying over 80 percent of the country’s arms imports over the past decade. And how does this benefit China?

By selling heavy armaments like tanks and submarines to a country, the importing country becomes reliant on China for a long time for training, maintenance, and repair. This reliance inevitably results in a certain degree of influence on the importing country. This makes it advantageous for China to be selling arms at low prices and on easy credit to countries bordering India as a way of checking India’s geopolitical ambitions in the region. For China, growing ties with Bangladesh serves the dual purpose of revenue from the sale of arms and checking Indian dominance in the region. The same argument can also be extrapolated for Chinese investments in other countries of South Asia. By investing significant amounts of capital in these countries, China is en-route the US like policy of global domination.